Testing Tensorflow code

Gain time and improve ML research by writing unit tests!

githubCode is available on github.

Introduction

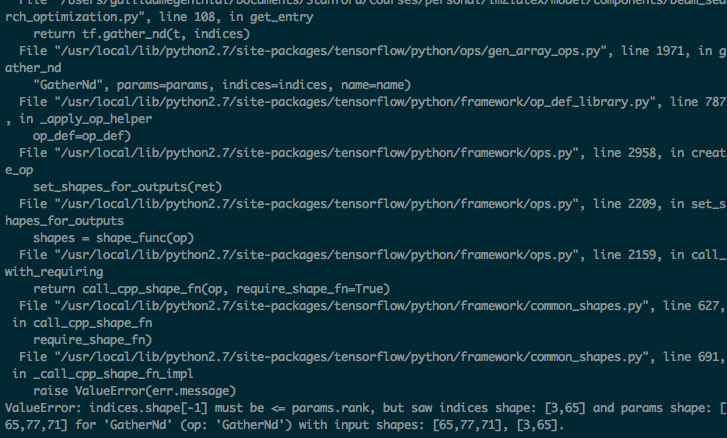

Who never experienced cryptic messages when developing some functionality in Tensorflow (or Theano, pyTorch, etc.)? I’m sure I’m not the only one having spent countless hours trying to understand these error messages to debug my code. Of course one gets better with time, and one is able to interpret them correctly in 90% of the use cases. But what about the other 10%? More importantly, even if don’t get any error and your Tensorflow code runs smoothly,

How can you be sure that your function performs the intended operation?

|

There are indeed cases where some minor mistake (or a big misunderstanding) in a call to some tensorflow primitive breaks everything. Mechanically it runs, but it is logically wrong and does not perform what you need. These non-breaking bugs can be extremely hard to nail down! And those are more usual than one might think! This is one of the main motivations for the recentely released Open AI Baselines. Here is what Szymon Sidor and John Schulman point out

Be wary of non-breaking bugs: when we looked through a sample of ten popular reinforcement learning algorithm reimplementations we noticed that six had subtle bugs found by a community member and confirmed by the author. These ranged from mild bugs that ignored gradients on some examples or implemented causal convolutions incorrectly to serious ones that reported scores higher than the true result.

In other words, if we listen to experienced researchers and programmers, the motivation for writing tests is deeply rooted in the quest for

- subtle bugs and correctness (for higher quality code and better research)

- time saving (as probably 150% of my programming teachers keep saying).

Guidelines

First, let’s briefly discuss our options regarding testing:

- run the whole pipeline on some input and examine the output

- adopt a new coding strategy, by breaking functionnalities into independent functions and test each chunk independently.

Option 1 might be the most common approach. As long as the code runs, overfits a small dataset and achieves good performance on a reference dataset, one might assume that it is correct. However, it does not address some subtle bugs and that’s why we’ll cover option 2.

In option 2. we’ll try to follow a few guidelines. First, we want to test our functions against the most general use-case possible. A good way of doing this is to write some randomized test that samples different inputs and check the outputs. The second principle is based on another simple observation: most of the time, the code that you write can be implemented in Numpy (or even Tensorflow) using a highly non-optimized, naive logic (with for loops for instance).

In other words, a good procedure is to follow these steps

for _ in range(number of random tests):

sample x

assert tensorflow_function(x) == naive_function(x)

As we never truly listen to people as long as our stuff works and also because we overestimate the difficulty of changing our habits (some might call it laziness),

let’s go over a quick example to help get you started!

Example

Now, let’s take a concrete example in which we want to extract entries of a Tensorflow tensor (advanced indexing is far from being a sinecure in Tensorflow). We want to write a function get_entry in Tensorflow that extracts entries of a batched tensor. In other words, given

- a tensor

tof dimension[batch, d1, d2] - a vector

indices_1dof dimension[batch] - a vector

indices_2dof dimension[batch]

we want to compute a tensor o of shape [batch] such that

Notice that without the batch dimension, this is just getting the entry $ (i, j)$ of a matrix $ A $.

Numpy code

The numpy code for this logic is straightforward, as we don’t care about performance

import numpy as np

def get_entry_np(t, indices_d1, indices_d2, batch_size):

result = np.zeros(batch_size)

for i in range(batch_size):

result[i] = t[i, indices_d1[i], indices_d2[i]]

return result

Tensorflow code

The same logic can be achieved in Tensorflow with the gather_nd function

import tensorflow as tf

def get_entry_tf(t, indices_d1, indices_d2, batch_size):

indices = tf.stack([tf.range(batch_size), indices_d1, indices_d2], axis=1)

return tf.gather_nd(t, indices)

Test code

To write a test, we’ll use the standard unittest library. First, import the library with

import unittest

and define a class that will contain our different tests

class Test(unittest.TestCase):

def test_1(self):

# always passes

self.assertEqual(True, True)

def test_2(self):

pass

# etc.

if __name__ == '__main__':

unittest.main()

In our case, we will just write one test, that follows the randomized logic. We first sample the size of the input, then sample a tensor t and the indices and then record if the output of the numpy and tensorflow functions are equal!

def test_get_entry(self):

success = True

for _ in range(10):

# sample input

batch_size, d1, d2 = map(int, np.random.randint(low=2, high=100, size=3))

test_input = np.random.random([batch_size, d1, d2])

test_indices_d1 = np.random.randint(low=0, high=d1-1, size=[batch_size])

test_indices_d2 = np.random.randint(low=0, high=d2-1, size=[batch_size])

# evaluate the numpy version

test_result = get_entry_np(test_input, test_indices_d1, test_indices_d2, batch_size)

# evaluate the tensorflow version

with tf.Session() as sess:

tf_input = tf.constant(test_input, dtype=tf.float32)

tf_indices_d1 = tf.constant(test_indices_d1, dtype=tf.int32)

tf_indices_d2 = tf.constant(test_indices_d2, dtype=tf.int32)

tf_result = get_entry_tf(tf_input, tf_indices_d1, tf_indices_d2, batch_size)

tf_result = sess.run(tf_result)

# check that outputs are similar

success = success and np.allclose(test_result, tf_result)

self.assertEqual(success, True)

Now let’s execute the .py file containing our test class.

|

… and success! We are glad to check that our non-intuitive Tensorflow implementation of this simple trick matches the numpy version. Now, we are (almost) sure that if something breaks down in the code, it won’t be this function’s fault!

Conclusion

I was surprised of how quick it was to implement a test (not more than 10 minutes), a time neglectible compared to what I spent coming up with the right implementation for our get_entry function! Thanks to the tests, you can iterate much faster and test a few solutions and possibilities for the arguments, without over-thinking about it, and get to the desired solution much faster! To go further in test-driven development, a common piece of advise is to write tests before leaving the workplace, for the functionnalities that you want to implement on the next day! That way, if you’re sure about the functionnality and can implement a naive implementation, you’ll be able to bootstrap in the morning and quickly focus on what really matters! There is also one benefit of TDD that we haven’t really mentionned so far: it encourages you to break your code into small functions that can be unit-tested. Your code will be more general, shorter and more reusable!

|